Sometimes, I feel the need to talk about why I write this blog and do stand-up comedy about scleroderma. It’s never my only topic, but it’s always there. We all contribute to the scleroderma fight no matter how little we think we are doing. Sometimes, just being a patient is all we can contribute and that’s always enough. Simply staying alive helps scleroderma patients who come after us because doctors talk to each other. I learned that when my son was born.

When we met my son’s pediatrician and told her how my son came into the world two months early, she said, “Oh, that was you? I heard about your case.”

It made me happy for two reasons:

1. Doctors discuss difficult cases within their community.

2. She knew what she was dealing with regarding the care of my son.

Even after medical school, medical providers continue to learn and teach others. Doctors talk about difficult cases with their peers and I never miss a chance to work with a medical student.

I’ve met doctors in random settings who worked with me as medical students. I’m surprised and flattered they remember me. I’m sharing it here because I didn’t know it at the time, but I’ve been raising scleroderma awareness and teaching doctors to listen to chronically ill patients for decades. Actually, we all do.

It would be amazing to walk into a hospital for care and have a medical staff that knows exactly what to do for my scleroderma symptoms and complications, but that’s a fantasy. In the real world, medicine is a practice, and not every clinician knows a lot about scleroderma.

And how could they? There are over eighty types of autoimmune diseases with intersecting symptoms and complications. And no matter what chronic illness we have, in addition to the specialist for that chronic condition we must have a team of specialists for our systems because let’s face it, it’s fucking complicated.

This doesn’t mean that I believe more about scleroderma shouldn’t be taught in medical school. It means that I am aware of the fact that scleroderma is one of the thousands of conditions and chronic illnesses that are out there. So when given the opportunity to teach, I say yes.

When offered the chance to work with medical students, I always say yes. It’s the easiest way to raise scleroderma awareness. Sometimes, medical students will just observe. Sometimes they’ll ask questions with their attendings present, and sometimes they’ll come in to practice asking patients questions for patient assessment.

There have been times in the hospital when I don’t feel up to talking and students are respectful about it. And maybe talking to medical students isn’t your thing and that’s great. You do you, Boo;-) My point is, that when we do what we are capable of doing, that is enough.

It’s hard to find a silver lining with a chronic illness. Here’s mine.

When we work to stay as healthy as possible or fight the good fight when necessary; we are not only helping ourselves to live longer, more fulfilling lives. We’re also helping scleroderma patients who come after us. We are proving that scleroderma is not a death sentence. We are proving that life isn’t over with a diagnosis. It feels like it, but it’s not.

Also, the nurses and doctors who treat us learn about scleroderma patients. The next scleroderma patient they treat will receive better care because of what they learned from us, even if all we did was receive treatment.

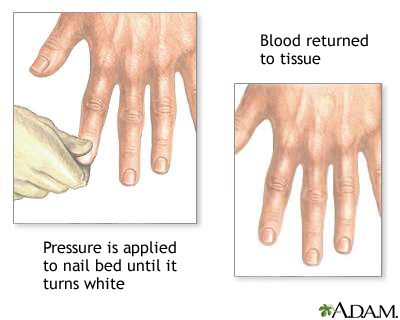

I don’t really remember my first Raynauds attack, but I remember the first time I saw it happen. In 1993, during the last year of my enlistment in the Navy, I had shore duty. Four nights a week, I attended EMT school at Miramar College. I was a “patient” for someone to practice leg splinting. After splinting, blood flow is checked by something called capillary refill.

Capillary refill tests the speed of blood return to a spot on our bodies- usually fingers and toes. When pinched, blood will disappear but should immediately return. In my case, my toenail remained white longer than it should have. Slow blood return is a symptom that indicates something is wrong. My big toe had a slow blood return and while the student EMT was checking the device, my toe turned blue.

The instructor came by to help us troubleshoot. She asked if I was diabetic. I was not. She advised me to get it checked. What she didn’t know is that I had been experiencing numbness and tingling in my fingers and toes with the smallest temperature drop for a little over a year.

I had already been seen by two rheumatologists at Balboa Navy Hospital and my blood tests were inconclusive. I was advised to stop smoking and stop taking birth control pills. I quit smoking and stopped taking the pill, but it kept happening When I followed up with my rheumatologists, they said it was probably nothing and just the way my body works.

The following October, I was seated on the examination table at the Madison Wisconsin Veterans Hospital. Two more rheumatologists were examining me. They looked through a jeweler’s loop just like the rheumatologists at Balboa did, but this time they had an immediate answer; scleroderma.

I was stunned. I had never heard of scleroderma, and neither did my boyfriend who drove me to the doctor that day. My first question was, “Will it kill me?”

Other than the name of my diagnosis, the rheumatologists had very little information about scleroderma and how it would effect me. I was told it could kill me in three years, or I could live to be one hundred.

My boyfriend said that I shouldn’t be consumed by whether or not scleroderma killing me, because I could waste all of my time worrying and end up getting killed by a bus instead. Great, not I’m scared of scleroderma and buses. But kidding aside, he had a point. Nothing had changed since walking into the doctor’s office, except I had a name for what was causing my fingers and toes to turn blue.

Twenty-seven years later, I am grateful to my ex-boyfriend for that perspective. It shaped my way of thinking more than I could’ve imagined back then. My only regret about that day is that I didn’t ask, “Can I drink with these meds?”